By Rick Anderson

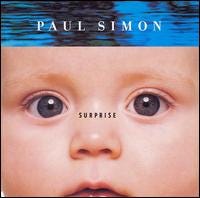

The cover of Paul Simon’s most underrated solo album, from 2006, shows an infant’s face staring out with an expression that might be wonder, or maybe bemusement, or maybe dull shock. The album’s title is Surprise.

This release offers an unusually unified body of songs, all dealing with the existential plight of the Baby Boom generation. This is a generation that was initially defined in terms of its infancy. As young adults, its members came to be known for their celebration of the innocence and naturalness of childhood. But now the Boomers are hitting retirement age, and can no longer avoid confronting mortality and the terrifying questions that come with it. While they’ve been following their bliss, expressing themselves, blurring the line that separates work from play, and having the cake of antimaterialistic hipness while eating the cake of unprecedented prosperity, most Boomers have at some point married and/or had children. Now they have grandchildren, and as the Boomers watch them grow, they find themselves standing on the threshold of an eternity that is invisible and mysterious, and that yawns open to engulf them at any moment. All that eternal-childhood stuff turns out to have been something of a cruel illusion.

Surprise!

To appreciate the richness and emotional complexity of Paul Simon’s new album, you must either be a Boomer or find a way to put yourself mentally inside the Boomer’s existential dilemma. It goes without saying that this isn’t your typical rock and roll. These aren’t songs about romance and passion and anger and ascendancy and triumph. They’re songs about what faith is and what we have faith in; about kids growing up and leaving; about wearing out one’s body and having nothing to replace it with; about whether existence is itself a meaningless joke; about how (and whether) the cosmos regards us and our endeavors.

Simon addresses these issues with his trademark combination of sharp wordplay and wry humor, but with what sounds very much like an underlying edge of despair. Although the songs on this album deal explicitly with issues of love, family and meaning, there are also frequent references to the boring minutiae of everyday life. “Weak as the winter sun, we enter life on earth,” he sings on “How Can You Live in the Northeast,” the album’s opening track. “Name and religion come just after date of birth.” (When and where? On the birth certificate, as in life itself.) “Beautiful” sketches out little details of bourgeois domesticity: a snowman, a go-kart, a water slide. But the growing family into whose life we’re peering is expanding in a particularly postmodern way: by adopting babies from various troubled and faraway countries. Both joy and grief are hinted at here: the babies are “beautiful,” of course, and the family is thrilled to have them, but how did they end up in the land of go-karts and water slides? What kinds of tragedy and bloodshed lie behind them on the path they took to America? (Perhaps none at all — and perhaps events of unutterable horror.) Racial politics adds a hint of uneasiness to this domestic portrait: “We brought a brand new baby back from Bangladesh/Thought we’d name her Emily.”

Both of those songs use descriptions of the mundane and the particular to suggest considerations of the infinite. But for Simon time is running out, and he no longer seems content to address what the scholar Hugh Nibley called the Terrible Question by hint and inference. On “I Don’t Believe” he deals with it head-on, though not without ambivalence. In fact ambivalence, with all its terrifying implications, is exactly what he’s facing up to on this track. Where other songwriters might take the easy way out, offering no conclusions while expressing some kind of vaguely waffling hope in the general beneficence of the universe or the goodness that lies in the hearts of human beings regardless of their ultimate place in it, Simon questions whether all of that stuff actually means anything and what the implications are if it doesn’t. His opening line is about the way that human kindness can lead us through the darkness — and then, as the music drops into a minor key, he brutally sings “But I don’t believe, and I’m not consoled/I lean closer to the fire, but I’m cold.” The ambivalence comes later, when he contradicts himself about what it is that he doesn’t believe: watching his wife combing her hair, he says “I don’t believe a heart can be filled to the brim/Then vanish like mist as though life were a whim.” Threaded through this meditation is an allegory: his stockbroker calls him up and tells him he’s lost all his money. Then he calls back, tells him it was all a mistake, and says that he hopes his “faith isn’t shaken.” By the end of the song, Simon is reduced to intoning the agnostic’s prayer: “Maybe and maybe and maybe some more/Maybe’s the exit that I’m looking for.”

The album’s emotional climax arrives gently, at the very end, with the gorgeous “Father and Daughter,” in which Simon addresses his daughter as she prepares to leave home. He tells her he can’t promise that there’s nothing scary under her bed, but he’ll promise what he can: to watch her shine, to watch her glow, and to “stand guard like a postcard of a golden retriever.” And that “as long as one and one is two/There could never be a father who loved his daughter more than I love you.” I first heard this song when I was the father of a teenage daughter myself, and I can still hardly think about it — let alone listen to it — without choking up. How Simon was able to sing it (with his son singing harmony in the background) is kind of beyond me. And there’s something to notice about his son’s voice as well: at the song’s beginning, thanks to producer Brian Eno’s electronic ministrations, it sounds like that of a startlingly talented baby; at the end of the song it has morphed into the voice of a mature woman.

Eno’s production on this album got much attention, and deservedly so: he takes Simon’s organically attractive melodies and acoustic guitar and fills in the spaces with a kaleidoscope of colorful electronic filigrees, African highlife guitars, skittering jungle breakbeats, and all kinds of subtly strange and melodically wonderful sonic extensions. Simon and Eno are an unexpectedly perfect combination. The music is purely enjoyable; the words are deeply affecting, and the questions Simon raises are ones that all of us have to face. That he is able to do so with such honesty, courage, and grace makes Surprise much more than just another fine pop album.